long

ICH Exhibition 3

-

NEWS

People on Vanuatu’s Malekula Island Speak More than 30 Indigenous Languages. Here’s Why We Must Record Them

: Indigenous languages preserve ways in which people engage with their environment. CCBY Royce Dodd, Author provided

Malekula, the second-largest island in the Vanuatu archipelago, has a linguistic connection to Aotearoa. All of its many languages are distantly related to te reo Māori, and the island is the site of a long-term project to document them.

Vanuatu has been described as the world’s “densest linguistic landscape,” with as many as 145 languages spoken by a population of fewer than 300,000 people.

Malekula itself is home to about 25,000 people, who among them speak more than thirty indigenous languages. Some are spoken by just a few hundred people.

Indigenous languages around the world are declining at a rapid rate, dying out with the demise of their last speakers. The UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues estimates one indigenous language dies every two weeks. As each language disappears, its unique cultural expression and world views are lost as well. Our project in Malekula hopes to counter this trend.

Malekula Languages

The work in Malekula began in the 1990s when the late Terry Crowley hosted a Neve’ei-speaking university student from a small village. The encounter inspired his interest in the island’s many Indigenous languages.

The Malekula project works with communities to facilitate literacy initiatives, often in the form of unpublished children’s books and thematic dictionaries. The research highlights the value of Indigenous languages as an expression of local cultural identity. The Malekula project is a response to the urgent need to record the island’s indigenous languages in the face of significant changes to almost every aspect of traditional life. These changes have brought indigenous languages into contact and competition with colonial English and French and the home-grown Bislama, a dialect of Melanesian pidgin. From education to religion, administration, and domestic life, Bislama is now often the language of choice.

Why is that a problem? The value of indigenous languages lies in the fact that they articulate the way in which people have engaged with and understood their natural environment.

Malekula has a 3,000-year history of human settlement. Each language spoken on the island encodes unique ways in which its speakers have sustained life. Indigenous languages preserve ways in which people engage with their environment.

Another fundamental aspect of indigenous languages is their direct link to cultural identity. In a place where distinctive local identities are the norm, the increasing use of Bislama reduces the linguistic diversity that has been sustained for millennia.

In recent times, the way of life for the people of Malekula has shifted from intensely local communities to broader formal education. Imported religions have similarly influenced local belief systems.

The same centralized governance that facilitates infrastructure development and access to medical care also affects the autonomy of small communities to govern their affairs, including the languages in which children are taught.

Traditionally, linguistic field research has produced valuable research for a highly specialist linguistic audience. Most scholars had no expectation of returning their research to the community of speakers. We initially followed this tradition in writing about the Neverver language of Malekula but grew increasingly dissatisfied with the expectations of the discipline. Looking to modern decolonizing research methodologies and ethical guidelines in Aotearoa, we developed the “first audience principle.” This means indigenous language communities should be the first to hear about any field research findings.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic and travel bans brought linguistic fieldwork to an abrupt halt. During this unwelcome hiatus from fieldwork with Malekula communities, it has been tempting to focus on more technical analysis for our fellow academics. But our obligation to communities remains, and we are developing new ways of working with our archived field data in preparation for the time when we can return to Malekula.

This article is based on the free flow of information, the creative commons from https://theconversation.com For the original source with additional links, please visit https://theconversation.com/people-on-vanuatus-malekula-island-speak-more-than-30-indigenous-languages-heres-why-we-must-record-them

03/12/2021

NEWS

People on Vanuatu’s Malekula Island Speak More than 30 Indigenous Languages. Here’s Why We Must Record Them

: Indigenous languages preserve ways in which people engage with their environment. CCBY Royce Dodd, Author provided

Malekula, the second-largest island in the Vanuatu archipelago, has a linguistic connection to Aotearoa. All of its many languages are distantly related to te reo Māori, and the island is the site of a long-term project to document them.

Vanuatu has been described as the world’s “densest linguistic landscape,” with as many as 145 languages spoken by a population of fewer than 300,000 people.

Malekula itself is home to about 25,000 people, who among them speak more than thirty indigenous languages. Some are spoken by just a few hundred people.

Indigenous languages around the world are declining at a rapid rate, dying out with the demise of their last speakers. The UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues estimates one indigenous language dies every two weeks. As each language disappears, its unique cultural expression and world views are lost as well. Our project in Malekula hopes to counter this trend.

Malekula Languages

The work in Malekula began in the 1990s when the late Terry Crowley hosted a Neve’ei-speaking university student from a small village. The encounter inspired his interest in the island’s many Indigenous languages.

The Malekula project works with communities to facilitate literacy initiatives, often in the form of unpublished children’s books and thematic dictionaries. The research highlights the value of Indigenous languages as an expression of local cultural identity. The Malekula project is a response to the urgent need to record the island’s indigenous languages in the face of significant changes to almost every aspect of traditional life. These changes have brought indigenous languages into contact and competition with colonial English and French and the home-grown Bislama, a dialect of Melanesian pidgin. From education to religion, administration, and domestic life, Bislama is now often the language of choice.

Why is that a problem? The value of indigenous languages lies in the fact that they articulate the way in which people have engaged with and understood their natural environment.

Malekula has a 3,000-year history of human settlement. Each language spoken on the island encodes unique ways in which its speakers have sustained life. Indigenous languages preserve ways in which people engage with their environment.

Another fundamental aspect of indigenous languages is their direct link to cultural identity. In a place where distinctive local identities are the norm, the increasing use of Bislama reduces the linguistic diversity that has been sustained for millennia.

In recent times, the way of life for the people of Malekula has shifted from intensely local communities to broader formal education. Imported religions have similarly influenced local belief systems.

The same centralized governance that facilitates infrastructure development and access to medical care also affects the autonomy of small communities to govern their affairs, including the languages in which children are taught.

Traditionally, linguistic field research has produced valuable research for a highly specialist linguistic audience. Most scholars had no expectation of returning their research to the community of speakers. We initially followed this tradition in writing about the Neverver language of Malekula but grew increasingly dissatisfied with the expectations of the discipline. Looking to modern decolonizing research methodologies and ethical guidelines in Aotearoa, we developed the “first audience principle.” This means indigenous language communities should be the first to hear about any field research findings.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic and travel bans brought linguistic fieldwork to an abrupt halt. During this unwelcome hiatus from fieldwork with Malekula communities, it has been tempting to focus on more technical analysis for our fellow academics. But our obligation to communities remains, and we are developing new ways of working with our archived field data in preparation for the time when we can return to Malekula.

This article is based on the free flow of information, the creative commons from https://theconversation.com For the original source with additional links, please visit https://theconversation.com/people-on-vanuatus-malekula-island-speak-more-than-30-indigenous-languages-heres-why-we-must-record-them

03/12/2021

-

NEWS

2021 Jeonju International Awards for Promoting Intangible Cultural Heritage

2021 Jeonju International Awards for Promoting ICH

The citizens of Jeonju are fully aware of the significance of intangible cultural heritage and its need for safeguarding. In particular, they have long recognized and emphasized its power as a resource for enhancing the social, economic, environmental, cultural conditions, as well as tending to the aspirations of all the people living in the global community.

The purpose of the Jeonju International Awards for Promoting Intangible Cultural Heritage is to encourage the model safeguarding practices of intangible cultural heritage in the global community regardless of nationality, ethnicity, religion, race, age, gender, or any other political, social, economic or cultural orientation. The model safeguarding practices of intangible cultural heritage shall include any effective method or approach.

The awards are open to Living Human Treasurers (practitioners), groups, communities, administrators, researchers, NGOs, and those who have made substantial contributions for promoting Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Eligibility Criteria

The awards shall go to individual or groups that practice good safeguarding practices of ICH.

Or the awards shall go to local communities, administrators, NGOs or other institutions that practice the modeling development, social solidarity, and cooperation throughout safeguarding practices of ICH.

Or the awards shall go to the individual or groups that have contained international visibility by raising cultural pride of their community during transmitting of ICH.

Or the awards shall go to the individuals or groups that achieve exemplary outstanding performance by practicing cultural diversity through the safeguarding and transmission process of ICH. The awards shall go to the individuals or groups that take the lead in good safeguarding practices of ICH in the global community regardless of nationality, ethnicity, religion, race, age, gender, or any other political, social, economic or cultural orientation.

Important Dates

February 1, 2021: Open to download 2021 JIAPICH application

March 1, 2021: Start of the application submission date

April 30, 2021: Due date for the application

July 1, 2021: Start of the verification process

July 30, 2021: End of the verification process

August 1, 2021: 2021 JIAPICH Finalist(s) Announced

September (dates TBD), 2021: JIAPICH Award Ceremony (online ceremony TBD)

Adjudication Criteria

Efficient cases of safeguarding practices of Intangible Cultural Heritage and of activating the power and its significance for the future development of the global community as well as for social cohesion, cooperation, and visibility of identity. A good example that has made a significant contribution to the viability of the Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Additional information about submitting applications and other important information is available here.

03/12/2021

NEWS

2021 Jeonju International Awards for Promoting Intangible Cultural Heritage

2021 Jeonju International Awards for Promoting ICH

The citizens of Jeonju are fully aware of the significance of intangible cultural heritage and its need for safeguarding. In particular, they have long recognized and emphasized its power as a resource for enhancing the social, economic, environmental, cultural conditions, as well as tending to the aspirations of all the people living in the global community.

The purpose of the Jeonju International Awards for Promoting Intangible Cultural Heritage is to encourage the model safeguarding practices of intangible cultural heritage in the global community regardless of nationality, ethnicity, religion, race, age, gender, or any other political, social, economic or cultural orientation. The model safeguarding practices of intangible cultural heritage shall include any effective method or approach.

The awards are open to Living Human Treasurers (practitioners), groups, communities, administrators, researchers, NGOs, and those who have made substantial contributions for promoting Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Eligibility Criteria

The awards shall go to individual or groups that practice good safeguarding practices of ICH.

Or the awards shall go to local communities, administrators, NGOs or other institutions that practice the modeling development, social solidarity, and cooperation throughout safeguarding practices of ICH.

Or the awards shall go to the individual or groups that have contained international visibility by raising cultural pride of their community during transmitting of ICH.

Or the awards shall go to the individuals or groups that achieve exemplary outstanding performance by practicing cultural diversity through the safeguarding and transmission process of ICH. The awards shall go to the individuals or groups that take the lead in good safeguarding practices of ICH in the global community regardless of nationality, ethnicity, religion, race, age, gender, or any other political, social, economic or cultural orientation.

Important Dates

February 1, 2021: Open to download 2021 JIAPICH application

March 1, 2021: Start of the application submission date

April 30, 2021: Due date for the application

July 1, 2021: Start of the verification process

July 30, 2021: End of the verification process

August 1, 2021: 2021 JIAPICH Finalist(s) Announced

September (dates TBD), 2021: JIAPICH Award Ceremony (online ceremony TBD)

Adjudication Criteria

Efficient cases of safeguarding practices of Intangible Cultural Heritage and of activating the power and its significance for the future development of the global community as well as for social cohesion, cooperation, and visibility of identity. A good example that has made a significant contribution to the viability of the Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Additional information about submitting applications and other important information is available here.

03/12/2021

-

NEWS

Drangyen, Bhutanese Instrument and Lessons

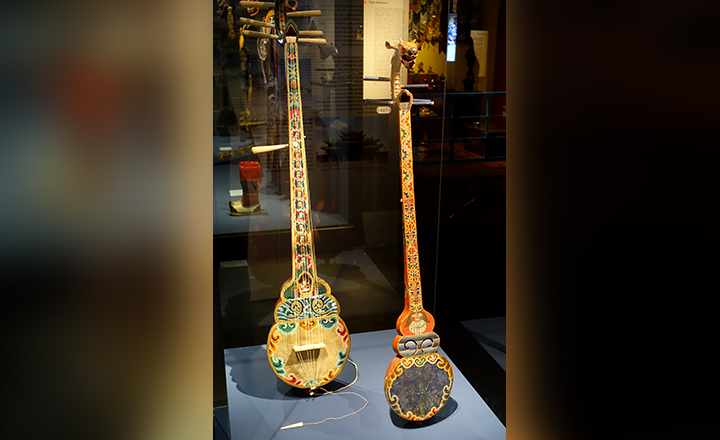

Two drangyens of Bhutan at Linden Museum (public domain image)

The Bhutanese lute, the drangyen, is the oldest and most well-known instrument of Bhutan. The word drangyen itself roughly translates to “hear the melody,” where dra means “melody,” and ngyen means “listen.” The drangyen is often used in religious festivals accompanied by folk dances and stories. Some date back to the eighth century CE when Buddhism was introduced to Bhutan.

The instrument is made from wood (preferably from cypress trees), leather, and yak bone and is about one meter long. Structurally, the top or head is intricately shaped like a sea monster to scare away evil spirits that may be attracted to the beautiful music that the instrument makes. The head stands upon a long fretless neck that attaches to a rounded body that pictures the goddess of music. The seven strings, which are made from the bark fiber of the jute tree, are played with a triangular plectrum made of wood or bone.

Kheng Sonam Dorji is a master folk musician of Bhutan. He has assembled a series of videos that show how the drangyen is made and how to play it. They are available in several lessons on YouTube. Visit the following links to find out more about the drangyen.

Drangyen Lesson -1: Brief Introduction ( with Eng Sub) – YouTube

Drangyen Lesson – 2(A) : Note Introduction & Tunning – YouTube

Drangyen Lesson – 2 (B) : Note Introduction & Tunning – YouTube

Drangyen Lesson – 3: Octave/Yangduen/ Saptak – YouTube

Drangyen Lesson – 4: Fingering & Note familiarization. – YouTube

03/12/2021

NEWS

Drangyen, Bhutanese Instrument and Lessons

Two drangyens of Bhutan at Linden Museum (public domain image)

The Bhutanese lute, the drangyen, is the oldest and most well-known instrument of Bhutan. The word drangyen itself roughly translates to “hear the melody,” where dra means “melody,” and ngyen means “listen.” The drangyen is often used in religious festivals accompanied by folk dances and stories. Some date back to the eighth century CE when Buddhism was introduced to Bhutan.

The instrument is made from wood (preferably from cypress trees), leather, and yak bone and is about one meter long. Structurally, the top or head is intricately shaped like a sea monster to scare away evil spirits that may be attracted to the beautiful music that the instrument makes. The head stands upon a long fretless neck that attaches to a rounded body that pictures the goddess of music. The seven strings, which are made from the bark fiber of the jute tree, are played with a triangular plectrum made of wood or bone.

Kheng Sonam Dorji is a master folk musician of Bhutan. He has assembled a series of videos that show how the drangyen is made and how to play it. They are available in several lessons on YouTube. Visit the following links to find out more about the drangyen.

Drangyen Lesson -1: Brief Introduction ( with Eng Sub) – YouTube

Drangyen Lesson – 2(A) : Note Introduction & Tunning – YouTube

Drangyen Lesson – 2 (B) : Note Introduction & Tunning – YouTube

Drangyen Lesson – 3: Octave/Yangduen/ Saptak – YouTube

Drangyen Lesson – 4: Fingering & Note familiarization. – YouTube

03/12/2021

NEWS People on Vanuatu’s Malekula Island Speak More than 30 Indigenous Languages. Here’s Why We Must Record Them : Indigenous languages preserve ways in which people engage with their environment. CCBY Royce Dodd, Author provided Malekula, the second-largest island in the Vanuatu archipelago, has a linguistic connection to Aotearoa. All of its many languages are distantly related to te reo Māori, and the island is the site of a long-term project to document them. Vanuatu has been described as the world’s “densest linguistic landscape,” with as many as 145 languages spoken by a population of fewer than 300,000 people. Malekula itself is home to about 25,000 people, who among them speak more than thirty indigenous languages. Some are spoken by just a few hundred people. Indigenous languages around the world are declining at a rapid rate, dying out with the demise of their last speakers. The UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues estimates one indigenous language dies every two weeks. As each language disappears, its unique cultural expression and world views are lost as well. Our project in Malekula hopes to counter this trend. Malekula Languages The work in Malekula began in the 1990s when the late Terry Crowley hosted a Neve’ei-speaking university student from a small village. The encounter inspired his interest in the island’s many Indigenous languages. The Malekula project works with communities to facilitate literacy initiatives, often in the form of unpublished children’s books and thematic dictionaries. The research highlights the value of Indigenous languages as an expression of local cultural identity. The Malekula project is a response to the urgent need to record the island’s indigenous languages in the face of significant changes to almost every aspect of traditional life. These changes have brought indigenous languages into contact and competition with colonial English and French and the home-grown Bislama, a dialect of Melanesian pidgin. From education to religion, administration, and domestic life, Bislama is now often the language of choice. Why is that a problem? The value of indigenous languages lies in the fact that they articulate the way in which people have engaged with and understood their natural environment. Malekula has a 3,000-year history of human settlement. Each language spoken on the island encodes unique ways in which its speakers have sustained life. Indigenous languages preserve ways in which people engage with their environment. Another fundamental aspect of indigenous languages is their direct link to cultural identity. In a place where distinctive local identities are the norm, the increasing use of Bislama reduces the linguistic diversity that has been sustained for millennia. In recent times, the way of life for the people of Malekula has shifted from intensely local communities to broader formal education. Imported religions have similarly influenced local belief systems. The same centralized governance that facilitates infrastructure development and access to medical care also affects the autonomy of small communities to govern their affairs, including the languages in which children are taught. Traditionally, linguistic field research has produced valuable research for a highly specialist linguistic audience. Most scholars had no expectation of returning their research to the community of speakers. We initially followed this tradition in writing about the Neverver language of Malekula but grew increasingly dissatisfied with the expectations of the discipline. Looking to modern decolonizing research methodologies and ethical guidelines in Aotearoa, we developed the “first audience principle.” This means indigenous language communities should be the first to hear about any field research findings. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic and travel bans brought linguistic fieldwork to an abrupt halt. During this unwelcome hiatus from fieldwork with Malekula communities, it has been tempting to focus on more technical analysis for our fellow academics. But our obligation to communities remains, and we are developing new ways of working with our archived field data in preparation for the time when we can return to Malekula. This article is based on the free flow of information, the creative commons from https://theconversation.com For the original source with additional links, please visit https://theconversation.com/people-on-vanuatus-malekula-island-speak-more-than-30-indigenous-languages-heres-why-we-must-record-them 03/12/2021

NEWS 2021 Jeonju International Awards for Promoting Intangible Cultural Heritage 2021 Jeonju International Awards for Promoting ICH The citizens of Jeonju are fully aware of the significance of intangible cultural heritage and its need for safeguarding. In particular, they have long recognized and emphasized its power as a resource for enhancing the social, economic, environmental, cultural conditions, as well as tending to the aspirations of all the people living in the global community. The purpose of the Jeonju International Awards for Promoting Intangible Cultural Heritage is to encourage the model safeguarding practices of intangible cultural heritage in the global community regardless of nationality, ethnicity, religion, race, age, gender, or any other political, social, economic or cultural orientation. The model safeguarding practices of intangible cultural heritage shall include any effective method or approach. The awards are open to Living Human Treasurers (practitioners), groups, communities, administrators, researchers, NGOs, and those who have made substantial contributions for promoting Intangible Cultural Heritage. Eligibility Criteria The awards shall go to individual or groups that practice good safeguarding practices of ICH. Or the awards shall go to local communities, administrators, NGOs or other institutions that practice the modeling development, social solidarity, and cooperation throughout safeguarding practices of ICH. Or the awards shall go to the individual or groups that have contained international visibility by raising cultural pride of their community during transmitting of ICH. Or the awards shall go to the individuals or groups that achieve exemplary outstanding performance by practicing cultural diversity through the safeguarding and transmission process of ICH. The awards shall go to the individuals or groups that take the lead in good safeguarding practices of ICH in the global community regardless of nationality, ethnicity, religion, race, age, gender, or any other political, social, economic or cultural orientation. Important Dates February 1, 2021: Open to download 2021 JIAPICH application March 1, 2021: Start of the application submission date April 30, 2021: Due date for the application July 1, 2021: Start of the verification process July 30, 2021: End of the verification process August 1, 2021: 2021 JIAPICH Finalist(s) Announced September (dates TBD), 2021: JIAPICH Award Ceremony (online ceremony TBD) Adjudication Criteria Efficient cases of safeguarding practices of Intangible Cultural Heritage and of activating the power and its significance for the future development of the global community as well as for social cohesion, cooperation, and visibility of identity. A good example that has made a significant contribution to the viability of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Additional information about submitting applications and other important information is available here. 03/12/2021

NEWS Drangyen, Bhutanese Instrument and Lessons Two drangyens of Bhutan at Linden Museum (public domain image) The Bhutanese lute, the drangyen, is the oldest and most well-known instrument of Bhutan. The word drangyen itself roughly translates to “hear the melody,” where dra means “melody,” and ngyen means “listen.” The drangyen is often used in religious festivals accompanied by folk dances and stories. Some date back to the eighth century CE when Buddhism was introduced to Bhutan. The instrument is made from wood (preferably from cypress trees), leather, and yak bone and is about one meter long. Structurally, the top or head is intricately shaped like a sea monster to scare away evil spirits that may be attracted to the beautiful music that the instrument makes. The head stands upon a long fretless neck that attaches to a rounded body that pictures the goddess of music. The seven strings, which are made from the bark fiber of the jute tree, are played with a triangular plectrum made of wood or bone. Kheng Sonam Dorji is a master folk musician of Bhutan. He has assembled a series of videos that show how the drangyen is made and how to play it. They are available in several lessons on YouTube. Visit the following links to find out more about the drangyen. Drangyen Lesson -1: Brief Introduction ( with Eng Sub) – YouTube Drangyen Lesson – 2(A) : Note Introduction & Tunning – YouTube Drangyen Lesson – 2 (B) : Note Introduction & Tunning – YouTube Drangyen Lesson – 3: Octave/Yangduen/ Saptak – YouTube Drangyen Lesson – 4: Fingering & Note familiarization. – YouTube 03/12/2021